On Brandy Hellville and the Cult of Fast Fashion and the Power of the Teenage Girl

If you're a member of Gen Z and grew up immersed in internet culture, chances are you can recall feeling personally victimized by Brandy Melville. My earliest memories of Brandy were during shopping trips to SoHo in the mid-2010s, stepping into their store to absorb the essence of the effortlessly cool girls who worked there. It was a ritual shared by many teenage girls; stopping by American Apparel hoping to see Tumblr-famous faces like Barbie Ferreira or Diana Veras, then heading to Brandy to catch Instagram indie girls like Apple Drysdale or Ellis Clare. I vividly remember the disappointment of falling in love with a pair of burgundy pants, only to find that Brandy's infamous "one size fits all" didn't fit me. These experiences reflect a deeper issue dissected in HBO's latest documentary, Brandy Hellville and the Cult of Fast Fashion, directed by Eva Orner.

This documentary doesn't just scratch the surface; it dives into the disturbing practices of Brandy Melville's chief executive, Stephan Marsan, revealing a nexus of white supremacy, size exclusivity, and exploitation of teenage (read: child) labor. Using research supported by organizations like The Or Foundation and Remake, the film sheds light on how Brandy Melville masks acts of discrimination, exploitation, and environmental degradation under the allure of Americana aesthetics and internet in-crowds. Former Brandy lovers are taking to social media platforms like TikTok to share their feelings after watching the documentary. The film has also made former employees feel safer telling their stories.

The brand, a niche staple to the chronically online since the early 2010s, rose in popularity amongst teenage girl online communities. Despite its chokehold on the culture, it has evaded scrutiny until now, as its one-time teen target market cohorts have come of age and, in part, shaped our present-day culture in which such big brands are held accountable. In decades past, however, Brandy’s manipulative marketing and exploitative labor practices slipped under adults’ noses as the brand used these girls’ online presence to help spread its agenda.

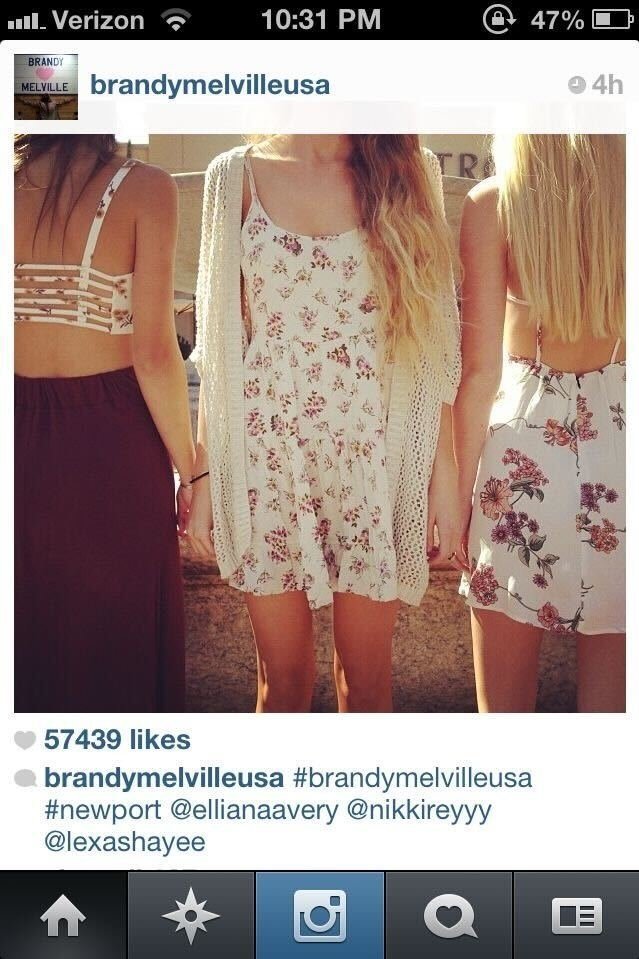

For anyone in their mid-to-late 20s, remembering the Tumblr days is nearly impossible without mentioning Brandy Melville, and the same is to be said for younger Gen Zs, who, even after Tumblr fell out of vogue, discovered the brand through TikTok. If Tumblr had the power to launch Brandy Melville into legendary teenage brand status, imagine what TikTok has done for the brand as we’ve entered a new stage of social media marketing. Early in the company’s existence, they used amateur photography by teenage girls to curate their Instagram content, often hiring these girls as photographers and models, leveraging social media as a primary tool for brand promotion. This strategy extended to consumers, as girls aspiring to emulate the brand's image purchased and showcased Brandy Melville's pieces on platforms like Tumblr and TikTok, where viral posts further fuel the brand's popularity and excessive consumption.

To understand the development of fast fashion to the point it has gotten to today, it's crucial to look at how social media–and the youth’s relationship to it–has been used strategically to manipulate consumer behavior. Instead of gathering to read the latest issue of Tiger Beat after school, teenage girls of the 2010s - 2020s found community in their clothing and internet aesthetic communities. Brandy Melville, like many modern fast fashion brands, infiltrated and turned our online communities into tools to manipulate and exploit girls and the planet, using them to spread subliminal and sometimes outright hateful rhetoric. It’s essentially digital Stockholm syndrome; we know fast fashion companies are evil at their core, but we feel a sense of community being part of a group of girls who love the same things. In Brandy Melville’s case, these things are California-coded clothing and photos representing a laid-back life anyone would envy. We can, and will, blame this on the disappearance of third places (like a physical space that would be safe and affordable for girls to gather after school). Both for better and worse, social media has become a tool for simulating them.

Brandy Melville understands that the most powerful influencer is not a huge celebrity or a Gen-Z darling like Charli D’Amelio; it’s regular teenage girls on the Internet—a group with enough power to help shift the tides around the rise of fast fashion. As a former teenage girl with a serious case of rage, we shouldn’t underestimate how much teenagers understand about the oppressive systems that govern our society, how passionate they can be about their causes, and their drive to create a more just world.

The message Orner leaves us with at the end of the documentary is IT: the best thing we can do to disrupt any brand is to stop buying from them. Now more than ever, we are witnessing the tangible impact of consumer choices. The effectiveness of boycotts and the potential for social media education are formidable tools for holding brands accountable. As consumers become more informed and conscientious, we demand transparency, ethical practices, and sustainability initiatives from fashion brands. Social media platforms serve as powerful avenues for education and activism, enabling individuals to mobilize for change and challenge the status quo (why else would our government want to ban TikTok? 🫢). If teenagers can influence other teenagers to buy pounds of Brandy Melville clothing, they can also influence each other to stop buying altogether; not out of a desire to fit in or be cool, but out of the inherent human ability to feel empathy for each other and protect our home planet.